“Faith of our Fathers” in Past Plagues: Mutual aid, vaccinations and social restrictions.

Arnold Neufeldt-Fast

With Maps and Illustrations by Brent Wiebe

Pandemics and plagues have been part of the longer Prussian-Russian Mennonite story. What can we learn from our ancestors and their responses as conservative people of faith?

- Danzig: Plague and Pestilence

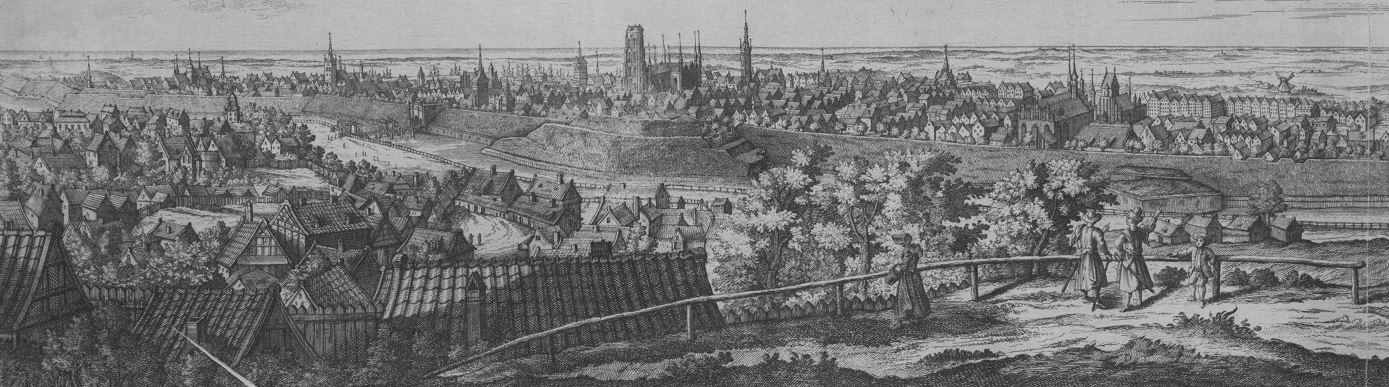

Russian and Prussian Mennonites trace at least 200 years of their story through Danzig and region–today Gdansk, Poland.

According to the Encyclopedia of Plague and Pestilence, the 1602 plague in Danzig killed 19,000.[1] In 1653, the city recorded some 600 plague deaths “weekly” for a time, with 11,116 deaths over the year. Four years later during the Swedish War, another 7,569 Danzigers died of the plague, compared to 2,569 births. And again in 1660, some 5,515 died of the plague, compared to 1,916 births in the city.[2]

We do not know how this series of plagues over seven years impacted the Mennonite community. However after a natural disaster caused dams to break and the lands to flood in 1667, a powerful government official for Pomerelia (near Danzig) argued that God was now punishing Poland and Danzig for its tolerance of Anabaptists. The official found broad support among the nobles in parliament for a plan to deport all Mennonites—which fortunately did not come to pass.[3] The memory of the sixteenth-century martyrs provided the lens for their suffering, with the publication of the Martyrs’ Mirror in 1659.

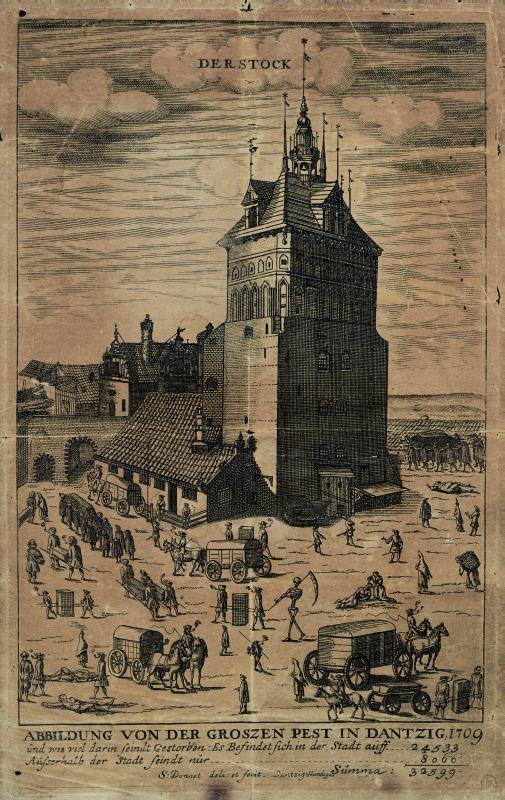

Danzig’s worst plague however hit in 1709.[4] The city had a population of about 50,000 and saw on average 2,000 plague-related deaths weekly for a period in September and October. City Council was forced to hire two Pest-Prediger (“plague pastors”) tasked to visit the sick and conduct funerals for the poor. Total plague deaths in Danzig that year: 24,533 persons, or about half the city’s population.

The few who recovered and were released from hospital were not allowed to go home, but rather required “to spend time in quarantine in empty houses in the outlying town of Petershagen”[5]—the location of the Danzig Flemish Mennonite Church and adjacent to the predominantly Mennonite suburb of Alt-Schottland.

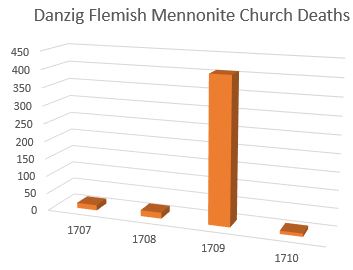

According to congregational records, there were fifteen deaths in 1707, seventeen in 1708, but an astonishing 409 deaths in 1709.[6] The congregation recorded thirteen deaths on September 18, 19, 20 alone–more than in a typical year. Ten days earlier (September 9), Elder Christof Engmann had died together with five other congregational members.[7] Visiting the sick was part of his call. In a congregation of some 1000 adults and children, 160 baptized members and 249 unbaptized adherents passed away that year.[8] On the final page of the congregation’s register of deaths completed a century later, the elder wrote: “There have never been as many deaths as during the plague of 1709.”[9]

How was the conservative Mennonite community prepared to deal with such calamities? How did events like these shape the spirituality of the tradition?

The 1709 plague led to a new “tradition” in the Mennonite church in Danzig: “to leave behind bequests for the care of the congregation’s poor,” and to organize for their burial. This continued for the next two centuries, according to a later elder.[10] This was a natural extension of their longer commitment to mutual care and aid. Both the Frisian and Flemish Mennonites had church buildings immediately outside the city gates (Neugartener Gate and Petershagener Gate respectively), and each also had its own poor house/ hospice under the direction of deacons.[11]

A medical report the next year stated with confidence that the plague came via Thorn, an area further south where Mennonites too had lived since 1586.[12] This 1710 report concluded with formulas for pharmacies, as well as a list of “do’s-and-don’ts.” The Danzig doctor warned against buying gimmick cures from drifters or market-criers. He observed too that those who visited many people, and those who were alcoholics were the first to die. Particularly harmful was the consumption of “Brandwein” (liquor; brandy) which Mennonites also brewed. “All stench and uncleanliness are very harmful,” as well. But the good doctor also adds that staying calm and trusting in God is a “great medicine” and recommended to all.[13]

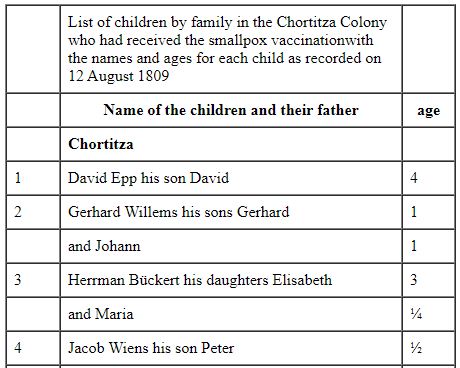

- Chortitza Immunization 1809.

In 1801, the number of deaths in the village of Chortitza was twice as high as the number of births due to a fever epidemic. In 1802 matters improved, with two births for every death in the colony as a whole.[14] Not many years later, most Chortitza Colony children–393 children from 205 families—mostly under six years of age were vaccinated for smallpox in 1809.[15] There is no record of resistance.

- Johann Cornies and the Cholera Pandemic, 1830

Asiatic Cholera broke out across Russia in 1829 and -30, and further into Europe in 1831. It began with an infected battalion in Orenburg and by early Fall 1830 the disease had reached Moscow and the capital.[16] Russia imposed drastic quarantine measures and much like today, infected regions were cut off and domestic trade was restricted.

“Government offices, schools, businesses, theaters, and other public places were closed and put under quarantine. Rumors started spreading, this time blaming authorities and healthcare providers for deliberately spreading the disease. When doctors recommended liquid antiseptics, like chlorinated lime solution or vinegar, for cleaning hands and faces, conspiracy mongers called them poisons. Doctors, and those who followed their recommendations, began to be brutally attacked.”[17]

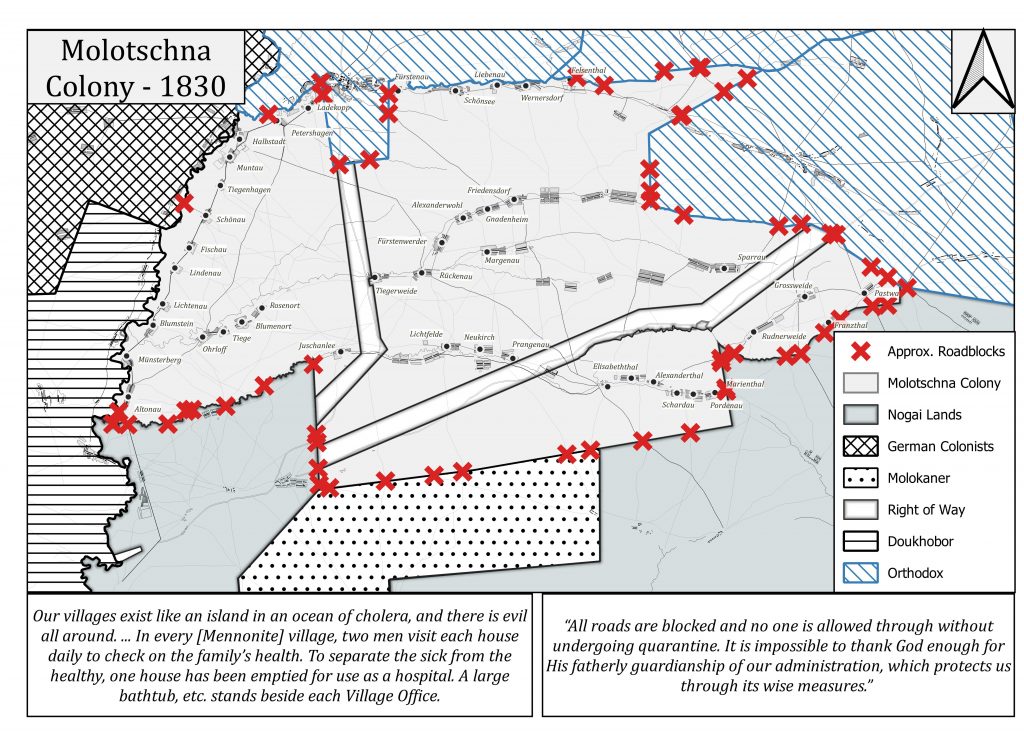

The disease reached the Mennonite Molotschna River district in Fall 1830, and by mid-December hundreds of indigenous Nogai deaths were recorded in the villages adjacent to the Mennonite colony.

When Molotschna Mennonite leader Johann Cornies first became aware of the nearby cholera-related deaths, he recommended to the Mennonite District Office on December 6, 1830 that all traffic and random contacts with Nogais be halted.[18]

Cornies praised the state’s decisive measures to isolate the virus and to enforce quarantines. Where there is good, wise and strong governance, Cornies saw the protective hand of God at work.

“All roads are blocked and no one is allowed through without undergoing quarantine. It is impossible to thank God enough for His fatherly guardianship of our administration, which protects us through its wise measures.”[19]

“If we follow these regulations scrupulously, the only thing left for us to do is to pray honestly and to submit to God’s Will.”[20]

What was important for Johann Cornies? Informed and decisive action, confidence that a sovereign God works through appointed earthly kings, together with prayer and submission to whatever may come.

On December 30, 1830, Cornies wrote to his friend Johann Wiebe in Tiege, West Prussia about the situation. He described the aggressive “precautionary measures” they had taken, but also offered a theological framework.

“Our villages exist like an island in an ocean of cholera, and there is evil all around. … In every [Mennonite] village, two men visit each house daily to check on the family’s health. To separate the sick from the healthy, one house has been emptied for use as a hospital. A large bathtub, etc. stands beside each Village Office.”

“We do not know what the future holds. Only the Eternal can see it. We must build on His grace and plead with Him to turn this scourge away from our empire and our villages.”

Cornies’s correspondence pointed repeatedly to the Tsar and his government as God-ordained, divinely directed and wholly reliable.

“With complete faith in the wisdom of our government, we await the Almighty’s ordinances without fear.”

“May every Christian, every thinking person harbour the personal conviction that whatever comes from God will serve our well-being. May this supreme wisdom divinely illumine man’s immortal spirit, created in His image, and cast light into the darkness of our earthly path.”

“We do not strive against God’s will by using our minds in taking precautions against disease and in battling disruptive natural forces. We are using our talents from on high, submitting them to His wise counsels and thereby praising His holy name. As you know, some people here consider precautionary measures to be sinful. Others continue to indulge in frivolity, even in this depressed, discouraging time.”[21]

Within a few months, the pandemic broke out in the city of Danzig as well, despite a 20-day quarantine on individuals and goods coming from Russia. On June 16, 1831, Prussia began to treat vessels proceeding from Danzig “as if coming from Russia.”[22]

In total, the pandemic took some 250,000 lives in Russia, with a 50% mortality rate among those infected.[23]

The Mennonite and German colonies of the region were spared a cholera outbreak. September 18, 1831: “Until now our community has been spared, although we have felt ourselves under siege since May … I consider no doctor to be God and no medicine as Saviour, but I firmly believe that if God does not give His blessing to our daily bread or our medications, they will neither nourish us nor heal us.”[24]

The global dimensions of the pandemic, the large numbers of deaths, the state enforced quarantines, the crippling economic consequences, the powerful resistance from the masses and the existential fear of death — all of these aspects bear a striking resemblance to our own times.

Perhaps there is something to learn from the faith and actions of our conservative ancestors in Prussia and Russia so many generations back.

[1] Encyclopedia of Plague and Pestilence: From Ancient Times to the Present, 3rd ed., edited by George C. Kohn (New York: Infobase, 2007) 87f. https://books.google.ca/books?id=tzRwRmb09rgC&lpg=PA88&vq=DANZIG&dq=danzig%20epidemic%201653&pg=PA87#v=onepage&q&f=false.

[2] Reinhold Curicken, Stadt Dantzig: Historische Beschreibung (Amsterdam/ Dantzigk: Janssons, 1687) bk. 3, ch. 31. https://reader.digitale-sammlungen.de/de/fs1/object/display/bsb10805961_00011.html.

[3] Anna Brons, Ursprung, Entwickelung und Schicksale der Taufgesinnten oder Mennoniten in kurzen Zügen (Norden, 1884) 258f. https://books.google.ca/books?id=BzU_AAAAYAAJ&pg=PR1#v=onepage&q&f=false.

[4] See weekly plague deaths (FIGURE xxx, far right column) from Johannes Kanold, ed., Einiger Medicorum Send-Schreiben, von der An. 1708 in Preussen, und An. 1709 in Dantzig … graßireten Pestilentz (Breßlau: Fellgiebel, 1711) 48f. https://archive.org/details/b30545687/page/48/mode/2up.

[5] Karl-Erik Frandsen, The Last Plague in the Baltic Region 1709-1713 (Copenhagen: Museum Tusculanum, 2010) 27.

[6] “Records of Prussian Mennonite Churches in the Vistula Delta: Births, Baptisms, Marriages and Deaths in the Danzig Church 1665-1943. Family Books 1 and 2 of the Danzig Mennonite Church.” Transliterated and digitized by Ernest H. Baergen. http://www.mennonitegenealogy.com/prussia/Danzig_Records.htm. Thanks to Maggie Schwichtenberg for pointing me to these records.

[7] “Records of Prussian Mennonite Churches in the Vistula Delta,” 100f.

[8] Hermann G. Mannhardt, Die Danziger Mennonitengemeinde. Ihre Entstehung und ihre Geschichte von 1569–1919 (Danzig, 1919) 82. https://archive.org/details/diedanzigermenno00mannuoft.

[9] “Records of Prussian Mennonite Churches in the Vistula Delta,” 130.

[10] Mannhardt, Die Danziger Mennonitengemeinde, 87.

[11] Mannhardt, Danziger Mennonitengemeinde, 104-106.

[12] Manasse Stöckel, Anmerckungen, welche bey der Pest, die anno 1709 in Dantzig graßirte, beobachtet wurden (Hamburg, 1710). https://reader.digitale-sammlungen.de//resolve/display/bsb10815757.html.

[13] Stöckel, Anmerckungen (last page; unnumbered).

[14] Dmytro Myeshkov, Die Schawarzmeerdeutschen und ihre Welten: 1781–1871 (Essen: Klartext, 2008) 133f.

[15] Tim Janzen, “Smallpox Vaccinations in Chortitza Colony, 12 August 1809.” Odessa Archives, Fund 6, Inventory 1, File 195. http://www.mennonitegenealogy.com/russia/1809.htm.

[16] John P. Davis, Russia in the Time of Cholera, Disease under Romanovs and Soviets (New York: I. B. Tauris, 2018) 40.

[17] Svetlana Zernes, “Russian Epidemics and Riots,” Russian Life (April 23, 2020), https://russianlife.com/stories/online/russian-epidemics-and-riots/; cf. also Davis, Russia in the Time of Cholera, 41f.

[18] No. 198, “Johann Cornies to Molotschna Mennonite District Office, December 6, 1830,” in Transformation on the Southern Ukrainian Steppe: Letters and Papers of Johann Cornies, vol. 1: 1812–1835, translated by Ingrid I. Epp; edited by Harvey L. Dyck, Ingrid I. Epp, and John R. Staples (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2015) 198.

[19] No. 200, “Cornies to Traugott Blueher, December 10, 1830,” in Transformation I, 200.

[20] No. 201, “Cornies to Andrei M. Fadeev, December 22, 1830,” Transformation I, 202.

[21] No. 202, “Cornies to Johann Wiebe, Tiege, West Prussia, December 30, 1830,” in Transformation I, 205.

[22] History of the epidemic spasmodic cholera of Russia (London: Murray, 1831) 245f. https://archive.org/details/b22478371/page/246/mode/2up.

[23] Davis, Russia in the Time of Cholera, 42.

[24] No. 239, “Cornies to Jacob van der Smissen, September 18, 1831,” in Transformation I, 244.

Excellent document! It is very fitting, and beneficial for gaining perspective on the pandemic that has spread around the globe in our time in 2020.